Though born in Colombia, Alejandro Londoño Montoya was an important part of the Venezuelan rock and metal scene with death/thrashers Epitafio and rap-metallers Agrésion. For the last two decades, however, his main focus has been his sludge/doom metal band Cultura Tres, which is a little more international in character.

“Cultura Tres was born in Venezuela”, Londoño clarifies. “But the only Venezuelan in the band is my brother, Juanma (De Ferrari). The idea was born in Maracay. Cultura Tres was kind of a heavier, darker side project my brother and I started while we were still in Agresión. It was the darker face of our creativity. After that, we decided to carry on with Cultura Tres, and end Agresión. That’s why it’s still a Venezuelan band, even though Paulo (Xisto, bassist) and Henrique (Pucci, drummer) are Brazilian, and I’m Columbian.

Before 2019, when Paulo started playing with us, we played doom metal. And nobody listened to doom metal in Venezuela. Venezuela doesn’t have a doom or sludge scene whatsoever. So a lot of people thought we were from Argentina, because Argentina has a very large doom/sludge scene, and we played in Argentina a lot at the time. But we just wanted to play, and Venezuela didn’t really have anything for us. The only band I know there that vaguely plays the same style, even though it’s closer to stoner, is Arrecho.

Since then, we have developed a little closer to a style that’s a little more popular in Venezuela. They do listen to thrash metal. That’s not necessarily what we do with Cultura Tres, but we did move a little closer to that. They don’t think we are as weird as they used to.”

No Real Memory

“I was four years old when my parents moved to Venezuela. Very young. At the time, I obviously didn’t play guitar yet. Or actually… I have seen a photo from when I was about two years old, playing a guitar. Of course, I have no real memory of it, but apparently, I used to play with that little guitar very frequently.

My mother was a singer/songwriter. She had already quit by the time I was old enough to know what a guitar was, so I have only seen photos of her playing. And it was her old guitar that she had somewhere around the house that I kind of started playing on. But I have never seen her play, which is a shame. It would have been very nice to see my own mother doing what she did in the past.

When I was 16 years old, I met my friend Miguel, and he was a huge fan of Metallica. Until then, there weren’t any bands that I was really into. There were a few songs on the radio that made me think: ah, that’s a nice song. But I wasn’t a fan of any bands. When I met Miguel, though, I got a cassette tape, with ‘Appetite for Destruction’ on one side and ‘…And Justice for All’ on the other. I immediately thought: what is this? This is amazing stuff!”

Over the Moon

“I immediately wanted to start a band. In the beginning, I thought I wanted to play bass, because it seemed easier. But of course, it isn’t easier at all. Also, I couldn’t get a bass from my family, because nobody expected that I would be very serious about trying to play music. Everyone thought it was a passing phase. I didn’t get any support from the rest of my family.

However, my grandmother thought: I will give him money for a guitar. Now, I wanted a bass, but we couldn’t find one that was cheap enough for me to buy, and I ended up buying a Gibson copy. My first guitar: a Gallan. I was over the moon. I was in love with that guitar, and I wanted to start a band.

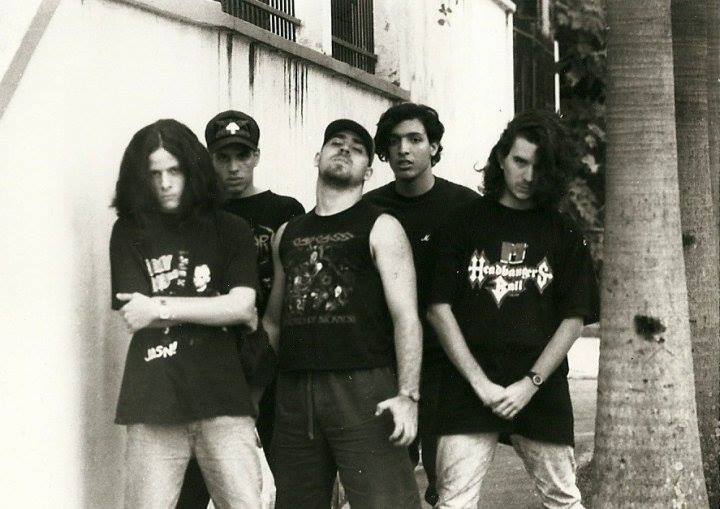

It wouldn’t be until about a year after buying the guitar that I had my first band. That band was what eventually became Epitafio, one of the first death metal bands of the region. It was kind of death/doom at the time. We couldn’t play any fast songs, because we weren’t good enough yet, so it was easier to play a bit slower. Also, everyone in the band was a fan of Cathedral at the time.”

The Thrash Impulse

“We were all friends from the same area in Maracay. We knew each other from high school, from things that got us together and had nothing to do with music. So we were completely different when it came to our influences. Our drummer really liked glam music, like Ratt, Poison, and Mötley Crüe, and he was a big fan of Queensrÿche. Rodnie (Perret, vocalist) was really into extreme music, like Cannibal Corpse.

Our bass player was the guy who gave me the tape, and he listened to more or less the things that I listened to. I was really into thrash. I was a huge fan of Metallica, Anthrax, Slayer and Sepultura. So I didn’t like glam, I didn’t like death metal, I wanted thrash to be the thing we played. But we all got together, because we had each other. We started a band because we were friends, and we wanted to do something together. So we needed to kind of find each other. And I was the thrash impulse of that.

Every time ‘Dominion’ (1994) became really thrashy, it was probably me bringing a riff in. And when it was really death metally, it was our other guitar player Ricardo (Vizcarrondo). Because Ricardo was really into Obituary and more extreme things. When he, together with Rodnie, would go in that direction, I would bring it back. Eventually, it became that middle ground that was a Malevolent Creation kind of feeling.”

The Most Evil Thing

“For a while, Epitafio was the support act for Gillman. Every time I saw Facundo Coral live, I thought: wow, that’s a real guitar player! Because he was older, and he looked like the guys we would see in magazines. We didn’t look like that. We were just getting out of high school, trying to grow our hair, but we weren’t allowed to have it long yet. Facundo was an icon for us.

Pablo Minoli grew up in Venezuela as well. He’s also part of that scene. He was actually part of the first death metal band that influenced all of us: Baphometh. Pablo played in that band with Franklin Zambrano. That was the beginning of everything for us. When that tape started to spread around, we all thought: what the hell is this? It was the most evil thing you could think of.

People would share these tapes from bands like Baphometh and SS. It was really underground. We were scared of these people. We didn’t know what they looked like, but it sounded like they were really evil people. I was really little at the time, so there were probably other things around, in other genres, but the really evil music was started by these two bands for me.

One of our biggest influences was actually a Dutch band, and it was Pestilence. Pestilence was mind-blowing. We were really, really big fans of that band. That was the first band that wasn’t thrash that I managed to absorb, to understand. It was musically pleasing to me.”

Creating a Genre

“The story of Venezuelan rock and metal music all comes down to Laberinto. That band could have gone really big if they were discovered a little bit earlier. They were pioneers. They were so mature. They were so different than anything else. They had their own vision when nobody had a vision. When we were all trying to copy stuff from other bands, they were creating a genre. None of us were that mature. None of us were even near that feeling of knowing what to do to be unique.

I remember hearing a song from them on the radio called ‘Radiation’. When I heard that, I thought: this is better than the bands that I listen to. Now, I can objectively say that the only difference is the production, obviously. We didn’t have the money, we didn’t have the means. The big bands were produced by the best guys in the best studios in the US. We had maybe free time at three in the morning at a studio that normally records salsa. And if you’re lucky, you’re friends with the people, and you can record with an engineer who doesn’t know how a guitar works for a decent price.

This Laberinto demo was a mixture of the lot of the big bands. They were just as good as Testament. Pablo Minoli is on par with Alex Skolnick. He’s an incredible guitarist. Far beyond the capabilities of most of the players I see around. And he was already that good back then! And they were putting this Latin percussion on it, which was unheard of at the time. This was before Sepultura did it, before Puya did it. Nobody would even think they could fit that in a song. And they made it fit! And it worked!

Raimundo Ceballos had the range of Michael Jackson at the time. He was incredibly acrobatic, in a way that not even the power metal or Iron Maiden people could do. We were puzzled. They were superior to the bands that we loved. Even though the recordings were extremely primitive, we knew they were on the way to becoming something really special.”

The Realism of the Performance

“Another band we really liked was Natastor. The first time I heard them, they blew me away. It was the first time that I heard extreme metal sung in our language that would make us get scared, because I could understand the lyrics. That became an influence for me in production as well. I could not only hear the aggressiveness in Paul Quintero’s voice, but I could understand every word, and be scared by it.

That became a goal. If you want to produce a band, it doesn’t matter how extreme the voice is: if you don’t understand what they’re singing, it’s worthless. And it was really through Natastor’s first demo, when I first heard that on the radio, I thought: oh man, this is so evil. Paul’s got great diction. Some people say it’s about the color of the voice, but the color of the voice is not going to last too long. A message is what stays.

Paul is probably unaware of how much I admired him all my life, because I don’t see him often, and we live in different countries. But Natastor really taught me a lot. Especially their early records. Because production is a double-edged sword. It can make things clearer and more apparently professional, but it could also deteriorate the brutality and the realism of the performance.

Natastor was one of the few bands that could play live as on the record. So those primitive recordings, I’m more impressed because of that. Because you can hear them play, and through that primitiveness, they come across as a really good band.”

Limited to the Interest of the Majority

“I have a lot to thank the scene in Venezuela for, because it made me the musician that I am today. If I didn’t have those years of experience there, I probably would have ended up doing something else. But I do think that Venezuela was overly influenced by what the Americans were doing.

That was something I started to realize when I started touring through South America with Cultura Tres. The rest of Latin America was really busy trying to find their own sound. You had the things that bands like Reino Ermitaño and La Ira de Dios from Peru were doing, and there were a lot of things going on in Argentina. Venezuela was too focused on imitating the American bands.

There were only a couple of styles of heavy music that were popular in Venezuela. There weren’t all these different branches and interesting things happening that you saw in the rest of Latin America. We had death metal, then it was metalcore; kind of limited to the interest of the majority. That was something I realized later, when I saw bands from other places on the continent. I thought: I wish we had that feeling of exploration, even if it results in things that aren’t popular.”

Not That Far Behind

“Because Epitafio was from a smaller city, we would never be taken seriously at the time. And that kind of gave us the itch to be proving what we were worth coming from that area. But we were lucky. I don’t know how. Probably a combination of factors that pushed us in the right direction.

Ricardo, a friend of ours we would visit all the time, had a big parabolic satellite receiver, and they were able to tape Headbangers Ball. It was a weekly ritual. There was no internet, but we would get these tapes passed around that he had taped for us, and that was a big thing, because we were not that far behind with the news. We would see video clips of other bands relatively fresh.

As people from a small town that nobody expects anything from, we had this need to prove ourselves. At the time, we were really dedicated, trying to get the right gear and everything. Because of that, the band was considered very much a surprise. People would see this band going to Caracas from a small town, and we would generate a lot of respect. And that felt very good for kids our age. Also, we would always try to get better at what we did. We were always thinking: what’s the next thing? We tried to be on top of the game.

We would do a lot of things differently than other bands, who maybe didn’t have access to these tapes. We had fanzines, but these weren’t moving images. So a lot of it was left to the imagination. We were very lucky that we had a lot of influences coming from the time that we used to have those tapes.”

Aiming for an Unrealistic Sound

“Another advantage was that we knew people who would go to the States often. We would just order things by fax, get it delivered to somebody’s house, and when that person would come back from the stage, we would get an amplifier. The first Randall stack that I saw in Venezuela was my brother’s stack. Everybody went crazy about the fact that there was a Randall half-stack there.

We were interested in sound as well. I ended up studying audio engineering. So we had a lot of lucky shots and a lot of extra interests that we put in the band, into getting the production right and getting things working fine.

Shows were really primitive, but if I look back, I actually envy those years. We used to think: it would be great if we had better lights or a better PA system. Living in Europe now, I see how pointless that is. There are youth centers here with two million’s worth of investments, and there’s twenty, thirty people watching a band. When I see pictures of those old shows now, there’s at least eight hundred people at any show. So the shows really had what was important.

Af the time, we didn’t see it that way. We were focusing on the shortcomings of the equipment, of the infrastructure. But in reality, nothing of that is important. What’s important is that every show is completely packed with people who love what they’re seeing, and who are traveling from all over the country to see it. And we had that going.

The sound was shit, it was half-working, the lights weren’t there, the stage was improvised, but it was packed. We were aiming for that unrealistic sound that ‘…And Justice for All’ or Fear Factory’s ‘Demanufacture’ presented to us. That was kind of our goal, and it was impossible to get there, because we didn’t have the tools at hand. But it used to sound so aggressive. It’s almost more like a seventies rock type of sound that we had.”

A Big Source of Exposure

“There were many places in the country that were developing their own scenes. I remember we used to hear from people from Maracaibo, in the northwest, and there were some people from Barquisimeto who had a separate scene. Everything was growing spontaneously in different areas. But the capital dominated. Those were the bands who got a lot of the spotlight before we arrived.

So we might actually have been the first band that wasn’t from Caracas that managed to get some traction, some exposure. All thanks to Paul Gillman as well. He was a big source of exposure, because he would play us on his program La Esencia. We were really proactive, and we were already recording. Because of that, they started to play our songs on that radio station.

Remember that this time was long before social media, so whatever was put in that spotlight was heard by the entire country right away. We had a lot of coverage on the radio, we were on TV every now and then, and eventually, we ended up opening for Sepultura in the ‘Chaos A.D.’ days. After that show, everybody knew us, because that show was huge. It was a big thing that Sepultura came back after their big success, and it was one of their first shows in Latin America. It was a stadium show, so it was really, really massive.”

Something Achievable

“Epitafio ended in a really weird way. We were doing great. We just didn’t know we were doing great. Especially after that Sepultura show, we were at the top of popularity for that genre. We were followed by a lot of people. But we were not really happy. And as we were used to doing, everybody was thinking: what’s the next thing?

I had big plans: I wanted to bring Epitafio to the States. I was already traveling to Tampa, Florida a couple of times. At the time, Florida was the Mecca. Everything we knew with death metal was recorded at Morrisound Sutdios. My dream was to work in Morrisound. So I went to the States for a year, to kind of see how it was. I lived nearby Tampa, in Sarasota, and I had a whole plan.

When I came back, I said: okay guys, we should just move to Florida, and this is what we’re going to do. But the guys weren’t really that enthusiastic about it. They didn’t think it was something achievable. The energy went down. Rodnie went to live in Isla de Margarita at the time, and we had to call each other to figure out when we were going to record or play again.

At the same time, I was already busy with my brother, because my brother wanted to start a band at the time. He wanted to play drums, but my mom said: no drums in the house, what if you play guitar like your brother? My brother was 14 years old at the time. I had a double stack made into a single stack, pushed that into his room, and gave him one of my guitars. He did very well very quickly. Within two months, he was already playing songs, and he wanted to start a band. So I reached out to friends of mine that didn’t have bands.”

Guiding Them Through the Steps

“This all happened when I was playing with Epitafio. We were playing shows, and I just thought it was a cute idea of my brother’s. He was playing with friends of mine who were a little bit older than me. They were starting to rehearse, and they needed help. And that’s really how I entered production. That’s basically became a producer at that time, and I didn’t even notice. Because I needed to think how this band could improve with their lack of experience, to get to a level that will sound okay.

My brother’s band started to very quickly go through the steps that Epitafio had done. I knew the steps, and I was just guiding them through that. Within a year, they had a demo, and the songs were already doing okay, the band was getting very popular very quickly.

The last Epitafio show – at least with me in it, because they reformed later – was basically a farewell show at a bar in Maracay. And it was so packed that there were people in the streets, and nobody could get in. It was honestly too small for the amount of people that Epitafio was able to pull at that time. But because we wanted to keep it all in our hands, it was our own production, and I got my brother’s band to open. They blew everybody away. It was a really great band to see live.

They were really fresh, because they were not playing extreme metal. What they did was closer to something like Biohazard or Deftones. Nobody understood what they were seeing, because they were used to the typical bands that we would normally have – classic metal, thrash, stuff like that. But these guys had Helmet-like guitar work, and both of them were rapping. The enthusiasm from everyone that night was immense.”

Not in the Public Eye

“After that, Epitafio was stuck. It wouldn’t go anywhere, it wouldn’t move, it wouldn’t have anybody pushing for the next idea. So my brother asked: why don’t you just join us? I was really reluctant in the beginning, because my dream was making Epitafio grow. And my vision of music was a little bit more evil, more sinister. That was what I enjoyed more. Agresión was lighter, more groovy, more influenced by what my brother listened to. Because my brother didn’t necessarily listen to rock. He was a big fan of House of Pain and Cypress Hill, and he just got into Helmet and Biohazard, and made his own thing.

So I liked just producing them. I didn’t want to play with them. But at a certain moment, I realized: I might as well join them. And that’s how I joined Agresión. People think I initiated the band, but actually, it was my brother. It was his band. They won the Festival Nuevas Bandas, a big band contest in Venezuela, in 1996, when I wasn’t in Agresión yet.

At the time, I was just really proud of my little brother impressing everyone with heavy music. Because heavy music was not in the public eye at the time. They were really successful among people who didn’t listen to metal necessarily. That was one of the things they had extra, that none of the bands we had could offer. We had to play for metal lovers, and my brother’s band could play in front of anybody.”

Bridge of Expression

“I made the decision to relocate to the Netherlands after I had a conversation with Raimundo Ceballos, the singer of Laberinto. He is a good friend of mine, and I would always see him as an older brother. He’s been a big light in my life. Laberinto was doing great in Europe. They started to play Dynamo, they were on Rockpalast, playing a lot of festivals, they got signed by Mascot… Things were going well for them.

That made me curious about the country they were at. I remember we thought it was Sweden, but then we would realize it was the Netherlands, and we thought: okay, what happens in the Netherlands? And then I started to investigate. At that time, the center of the metal world was the Netherlands. Everything was a little office in Bussum-South. Because that was where Roadrunner was. And Roadrunner Records was the only label that was putting all this stuff out there. They wouldn’t be scared of putting a band out that would scream instead of sing.

They were the real bridge for all this expression in heavy music. That’s when I realized that all my favorite records said ‘B.V.’, because it was Roadrunner The All Black B.V., and most of the posters that I had said ‘Live at Dynamo Open Air, Eindhoven’. So I thought: what the hell am I doing trying to go to Florida if all of these Florida bands are actually signed by this label in the Netherlands? So I thought: we’ve got to go there.

And I came just because of that. I had a talk with Raimundo, who more or less explained me how to get a hold of starting to play and everything, and then I just grabbed my guitar and took a flight to Amsterdam.”

That Evil Gremlin

“But we still played in Agresión. Agresíon was really lucky at the time, because MTV and The Box and TMF (Dutch music television stations) really liked our music, and they were starting to play our music. We were starting to get fairly popular in the Netherlands, so we went on with Agresión for a long time. We were playing everywhere. It was going very well.

At the time, it was really our band, and we gave it all. I don’t regret that, although I always had that evil gremlin on my shoulder telling me: you have to make evil music. And at a certain moment, he won, because I decided: let’s just do other things. That’s when we stopped with Agresión, and we started with Cultura Tres.

Before that, Cultura Tres was a side project that my brother and I had, where we would just make really evil types of riffs, and I would fake being John Tardy. We would put it on a four-track tape, and call it Cultura Tres. We were not really aiming to be successful. We were just following the exploration of how to make music more introspective, more evil, more abrasive. All the things we didn’t explore with Agresión at the time.

These days, it’s almost like they are joining together. There is stuff on the new record (‘Camino de Brujos’, 2023) of which my friends have told me that it sounds a lot like Agresión. We first had to explore the extremes separately, and now we’re joining them. We went from doom to whatever the latest record is. I don’t know, ‘South of Heaven’? Sometimes it’s just really blasting. Paulo plugged his stuff, and we already had a lot of influence from Sepultura, but now he is a very literal influence of Sepultura pushing towards the more aggressive and punky side of things.”

Like an Accent in a Foreign Language

“We had that package of my brother being very groove-driven, making things work for people who were not metalheads, and I have this more evil type of approach coming from Pestilence and thrash metal. But along the way, when we started as a doom band, Agresión fans were not really welcoming to us, because they would come up to us and as us for things we didn’t want to play.

We started to play with these bands that were doom, sludge and stoner. And they jam; they improvise. They make things more like people did in the seventies. We played at the first Desertfest in London. We saw all these people that we didn’t even know were making music, because they were from a different scene. Bands like Los Natas and Banda de la Muerte from Argenina, who would jam big, bluesy things.

Then we abandoned that scene a little bit, because we are now making things that sound a little more like thrash metal again, and we are very powerful and focused. But we still have that luggage. We still have the feeling: now it can go a bit trippy and be psychedelic. We thought we were making a statement with a more thrash metal-oriented album, but it will always go somewhere else. It’s like an accent in a foreign language. You don’t know that you have it, but you do.

We got to this place where it’s really solid, but then there are bridges, intros or outros where it’s really mingling. Paulo has that need as well, because he likes a lot of seventies rock, and that is really the music he plays in his car. But he has been playing with Sepultura for forty years, which has a different intention, so Cultura Tres is the way for him to bring that out. Things can become heavy, then psychedelic, and then heavy again.”

Analyzing Steps Taken Naturally

These days, Londoño is also active as a producer. “I think it started out of coincidence”, he admits. “When I was driven to make my brother’s band better, even though I didn’t play in it, I had the objectivity by not being part of the band, but I had the experience through Epitafio of what the steps are. When you do things naturally, you don’t really realize what you’re doing. It’s very difficult to explain to somebody how to pedal on a bicycle. You just do it. So when you really need to explain it, you need to analyze what you did.

That’s why my first step in production was analyzing what Epitafio did. Then I went through various stages: learning how to tune the drums, how the guitar has to sound, calibration, the gauge of the strings, and the songs have to be this long… It really made me analyze the steps we took naturally, and they became more rationalized, and I started to do it with Agresión. I think I did pretty okay, because they were together for only eight months when they won the Festival Nuevas Bandas.

I studied audio engineering, but I studied broadcast audio, for things like TV. I got familiar with some equipment, but not really that deep. Later, when I was touring as a front-of-house engineer for various bands, I got more familiar with that. And when the CD era stopped, and the labels were cutting down on everything, that was when I was forced to learn how to do it myself, because there were no budgets anymore to get you to a studio for a new record.

Younger people wouldn’t know that this happened, but between 2005, when the industry went completely bankrupt, until now that it’s starting to recover, that was the time when all bands had to figure out how to do things themselves. During that time, I went really deep. I was already working for jazz bands as a live sound engineer, but that was when I was starting to be asked by people who were in the same situation if I could record and mix them.”

Something to Compare It To

“It was in 2004 when I started producing. And I think it was by 2012 that I had the feeling that I knew what I was doing. I had imposter syndrome for a very long period of time. I always felt like I was doing the best that I could do, but it wasn’t good enough. Keep in mind: I was someone who lived through the times of the big budgets of the record labels. And that made me realize that that was the reason: I had something to compare it to that most people would never even know existed.

The mid-segment of artists already thought that I was doing was good enough. But it wasn’t good enough for me, because I already knew how else things could sound. I had friends like Attie Bauw., who was someone who had helped us in the past, and who is probably one of the people I look up to. Because he was the guy who really guided me into working in studios. Attie was a great friend, and a really good help in getting me going.

Those were the things I looked up to. I thought: I don’t even sound nearly as good as Attie. So I considered myself as someone who could help, but I never thought that I would ever be doing anything to his standard. But then I started to realize that people liked the things I was doing. That made me much more confident about my production work.”

Leave a comment