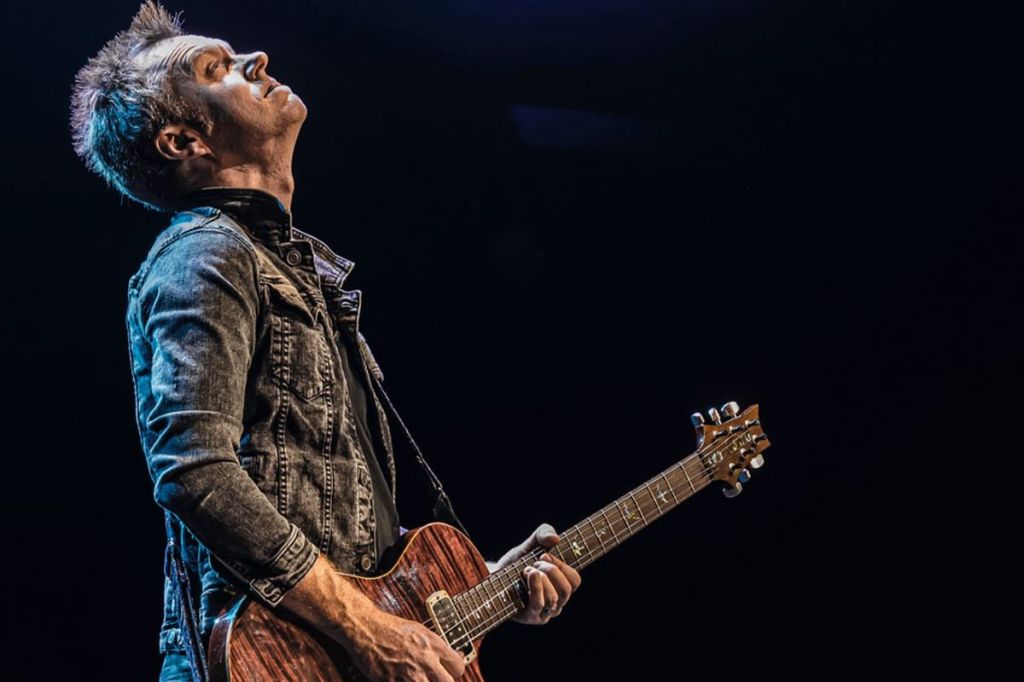

Joining hard rock legends Deep Purple introduced Northern Irish guitarist Simon McBride to a significantly larger audience than ever before. The release of ‘Recordings 2020-2025’ gives his new audience a chance to get familiar with McBride’s own material and the way he handles cover songs. McBride sheds some light on the new recordings and his near-lifelong relationship with PRS.

“The idea for ‘Recordings 2020-2025’ came very last minute”, McBride admits. “A lot of the songs were B-sides of singles and stuff I had released before. And then there was some stuff that hadn’t been released yet. Especially with the cover stuff. Around the same time, we actually went into the studio in the middle of a tour, because we had three or four days off, and the record company wanted us to record our whole live set we were playing at the time.

So this album is like a tale of two halves. One side is the produced cover versions, properly done in the studio, whereas the other half of it is a lot of older stuff which I used to play live, which we tracked live in one or two takes. We had all this just sort of lying around. We’re not doing much with Deep Purple this year, so we had a chat with the record company, and suggested to put all that stuff that’s unreleased out. It was too good not to be put out there. In my opinion, anyway.”

Exhausting Every Angle

“It’s different than what I would normally release, because of the choice of covers. I do not like doing direct copies of other people’s songs. One of the big questions I get asked all the time is: why did you not do a Deep Purple song? Well, one: I’m in Deep Purple. And two: I wouldn’t know what to do with them. Because at the end of the day, you’re taking one rock song, and kind of turning it into another rock song. My brain just doesn’t work that way.

Dave Marks is the bass player on this record. He is very much a big part of the production as well. We sat together and said: let’s go outside the box. What else do you listen to? Dave brought ‘Lovesong’ to me, and I just couldn’t hear anything for it. I didn’t know what to do with it. But as we did with every other song, we exhausted every angle we could. Just to see what we could do.

For a laugh, we just said: let’s just cut the thing in half, tempo-wise. And as soon as I played the melody, there was something there. It instantly reminded me of a Gary Moore melody or something. Like ‘Still Got the Blues’ or something like that. It ended up like this big ballad. Even though it is sort of already a ballad when you listen to the lyrics.

It’s easier for me to take a pop song, like ‘Ordinary World’, and turn it into a rock song, because it’s never been done as a rock thing before. Because if you look at any song, if you strip it right down to the melody and the chords, strip away all the production and the extra instruments, you can add heavier guitar and all that sort of thing, and move it into rock. I can take that song and put it in my set, and it wouldn’t feel out of place.”

Competing with the Originals

However, that’s not a hard and fast rule for McBride. “There’s ‘Kids Wanna Rock’, which was chosen because that was basically one of the things I ever learned on a guitar”, he says. “I didn’t know what I was going to do with it, because the original is a rock song anyway. But I remember listening to that one at the time, and for some reason, the Foo Fighters came on the radio or Apple Music. And it was ‘The Pretender’. I thought: ah, let’s take that idea and put it into ‘Kids Wanna Rock’!

And then there was The Kinks song, ‘I Gotta Move’. When you listen to the original of that, that’s a typical fifties, sixties rock ‘n’ roll thing. I played the riff, and I said: let’s slow it down and turn it into something by Rage Against the Machine. And it worked! I like to do stuff that’s different like that. Because if I hear a cover version, and it’s exactly the same, I would be very disappointed. Then you’re just competing with the original. And you can’t compete with the original. It’s there. It’s set in stone. It’s history.

So I always wanted to give people something a little bit different to listen to. Like ‘The Stealer’. It’s pretty much as the record, but then I went: no, let’s change it up a bit. So we changed the chorus part. We use the same things they’re using, but we just embellished them a little bit, and then added a key change in the solo. I had this whole mad Lydian part at the end. It’s a mad mode.”

In Glorious Stereo

“My set-up for my solo stuff is pretty much the same as what I use in Deep Purple. I’m a creature of habit, really. I love new gear, but I always end up back with the same thing. When I play live with my own thing, my rig is basically a smaller version of my Purple rig. And what I mean by that is that I’ve only got two 2×12’s instead of six. Because obviously, the venues I play in are a lot smaller than the big arenas and stadiums we play with Purple. Plus: I have to lift them, haha!

Guitar-wise, it’s exactly the same. I don’t bring as many guitars for my own stuff; I bring about two. I have three pedalboards that are exactly the same. I use a lot of the GigRig switching systems. Which is great, because it keeps the signal pure from the guitar to the amp.

I use a stereo system all the time. I always used to do mono before, but then Covid hit, and I was sat in my studio for two years, listening to everything in stereo, because a lot of it was played through the monitors. And once I got used to that, I couldn’t go back to mono. Plus, with my own band, I use in-ear monitors, so it’s stereo, and it’s glorious.”

Hovering Around

“At the moment, I have a modified Engl amp, which is the main workhorse, and then I just have a stereo power amp. So basically, out of the Engl, they all get sent into the board, and then to the GigRig G3, and then one gets back to the return of the amp, while the other goes into the power amp. So the sound is really coming from the Engl amp, and then it’s just split into another power amp, which is essentially the same power amp, but in the Engl head for the one side.

Sometimes I use different power amps. I’ve got an old Carvin T100 power amp which I’ve used for years, which is great. And I also have a Seymour Duncan power amp. I use it because it’s light as well. On the Deep Purple rig I’ve used, Engl has set up power amps as well. A rack power amp. It’s really just that: the Engl head into the pedalboard through a bunch of effects.

I use TC Electronic stuff, Boss stuff, Line6, DigiTech… I use JAM Pedals a lot. I love their stuff. The Uni-Vibe, the chorus, and I use a pedal of theirs called a Boomster, which is just like a line boost, which is what I use for most solos. The reason why I like that one is because it doesn’t do anything to the sound. It’s like somebody walked up to your amp and turned the gain up.

Some boost pedals might boost a certain frequency more. In Deep Purple, I can always tell when Tobi Hoff, our sound guy, is not happy, because he would be hovering around in front of the stage, and I have to go: what’s wrong, Tobi? And he’ll say: the boost pedal is boosting too much around 2K. But when I got this one, I haven’t seen him around the front of the stage, haha!

That’s a great sound man: somebody who can pinpoint certain things that may be wrong with the guitar frequencies. Because then he would have to counteract that with the desk, which he doesn’t want to do, because he wants it to be as natural and as pure as possible. Sometimes it’s hard for me to hear on stage, because it’s so bloody loud.”

A Flat Formula

“PRS Guitars I have used for years. It’s like family to me. I could pick up a Strat, or I could pick up another guitar, and it would just feel weird to me. Everyone gets used to a certain feel of a guitar. I have my own signature models which Paul Reed Smith makes me. They’re great. They never break. They never let me down. It’s just perfect. I started using the Vega-Trem, because it’s brilliant for a lot of the whammy bar stuff.

What I like about PRS guitars is that they allow me to create the sound. No matter who plays a Strat, it’s always that Strat sound. Whereas I find that a PRS is a very kind of flat formula. It’s like you’re a singer, and you go into a studio, and you have a very flat-sounding microphone: it allows the vocals to create the sound. So I can achieve a brighter sound on a PRS, or I can make a smoother, mellow sound if I want. It really just depends on how hard you hit the strings.

I hit very hard sometimes. I like for the amp to be set up quite dark, because I know I hit quite hard, and that natural kind of attack, presence, and treble would come through. If I had my amp set up with the treble right up, it would sound horrible. It’s really down to your fingers, and how you make a guitar or an amp sound. If I plugged into Steve Lukather’s rig, unfortunately, I would sound like me and not him. When Jeff Beck was still alive, he could plug into the wall and still sound like Jeff Beck.”

It’s About Support

“When I met Paul Reed Smith, I was about fourteen, roughly. I think when he saw the state of my guitar that I had at the time, he thought: I need to make you a guitar, a decent one. Paul’s a lovely guy. I still talk to him every other week. The whole company is very supportive. For one: they make amazing guitars. They’re just rock solid. But it’s more than that.

It’s not necessarily having a million guitars, it’s more about the support that they give you. I could be anywhere in the world, and I could phone up PRS and go: I’m stuck, I need a guitar. And they’ll just turn around and say: where and when do you need it? It’s as simple as that. Having that support. They will just ship it out to you, no matter what you need.

When I first got asked to do the Deep Purple thing, I was in a bit of a panic. Because when I first stepped in, it was literally: right, you’ve got to jump on this tour in about to weeks’ time. I needed more guitars, so I phoned PRS up, and they said: we’ll be there, not a problem.

I have been with them for years, and I did clinics with them for a long time when I was a kid, right through my teens and twenties. Right through my thirties even. I’ve just always been a part of it. So for me to go somewhere else these days would be very strange for me. I couldn’t do it. They’re a big part of my career.”

Perfectly in Tune

“Where I am now, it wouldn’t have happened without the help of PRS Guitars. Because that’s how I met Don Airey. Don runs this little charity festival in his home town, and Don phoned up Gavin Mortimer, who was the head of PRS Guitars Europe. Also, Gavin is the godfather of Don’s son. Don was looking for someone to open up his festival, and Gavin said: I know a guy. And he suggested me.

Ever since that, it kind of steamrolled from there. Don asked me to play on his stuff, and then I toured with Don. And then we did the Ian Gillan thing. And that eventually lead to a small band called Deep Purple.

I have eight PRS guitars on the road, split between two rigs. So four in each rig. I don’t need any more than that. I mean… That’s probably way too many for me. The only reason I use different guitars on the road is strictly because there’s some songs, let’s say ‘Smoke on the Water’, where I start on my own, so the tuning needs to be perfect. Tommy Alderson, my guitar tech, will come in and it’s perfectly in tune, and it’s ready to rock.

There’s one song in which we tune down, called ‘Bleeding Obvious’. But foremost of the time, I will play my Singlecut or my 24-08. The 24-08 that I use live – that’s not my personal, it’s just a stock one – has a neck that is a little bit slimmer than mine. So when I get lazy. I start playing that one, haha!”

Creating Something from an Influence

“Over the years, I’ve done a lot of session stuff. Pop stuff, rock stuff, hard metal stuff, country stuff, Irish stuff… I’ve done lots of different things. But I think that’s good for every player. That’s how you create your own sort of style. If I was to give some sort of solution to ‘how do you create your own sort of style’, it’s playing lots of different things. Because if you just play guitar music and rock music, you will sound like everybody else.

The guy I always use as an example is Steve Lukather. When you listen to a saxophone player, and you listen to Steve, you can see where he gets a lot of his little things with bands. So I kind of take that same approach. I live in Ireland, so there’s a lot of pipes, like the uillean pipes. When they play a note, everything always sounds squeezed because of the air in the big bag. There’s this little crescendo into air being lilted to play. And I thought: let me try to do that. Which I’ve tried over the years, and it has eventually become just a normal part of my everyday playing.

It’s the same as the covers: I had to look outside the box to make it interesting. It’s the same with whatever you’re playing. You just have to look outside of what you listen to every day. You never know what you might take from it. Sometimes when I go write stuff, say I’ll go into the studio with the intention of writing some music, and I come with nothing. Then I’ll go: alright, I’ll go listen to something completely different. Maybe an old classical piece by Mozart or whatever.

Then you go: I wonder what it would sound like if I took that, played it on guitar, slowed it down, changed this, and changed that. And there you go: you’re creating something from an influence. You’re not copying or stealing. You’re just basically taking the idea of it and making it your own. But it’s something you never would have played before. I believe you’ve got to learn from everywhere.”

Just Got Slower

Despite his large and varied resume, McBride’s recording debut was actually with Belfast-based heavy metal band Sweet Savage, on their 1996 album ‘Killing Time’. “I was sixteen when I did that first record with them”, he says. “And I still do stuff with them to this day. They’re still going, in a roundabout way. They just don’t do a lot anymore. Vivian Campbell is off with Def Leppard and stuff.

Ray Haller, the singer, is still a good friend of mine. I still see him every other week. That was great craic at the time. Don’t ask me to play any of that stuff now. I couldn’t do it. I listened back to some of the stuff I was doing when I was sixteen, all the really stuff, and I go: yeah, no. I couldn’t do that now. I’ve matured, as they say, over the years. I just got slower. That’s it, haha!”

An edited version of this interview appeared in Gitarist 410 (May 2025)

Leave a comment