Frequent readers of this blog probably would not be able to tell, but I do listen to a decent amount of jazz-related music. It just doesn’t get reviewed here all that much, because my review format does not work very well with jazz releases. Jazz generally tends to be relatively bare bones on the compositional side, having its focus mainly on the interaction between the musicians involved. Exceptions exist, we might actually go into a few in this article, but most jazz is too improvisation-based to lend itself well to having its compositions picked apart like I do in most of my Album of the Week reviews. Especially not on the more traditional side of the genre.

This article exists for two reasons. One is simply to give myself an excuse to write something about jazz releases I enjoy without having to force it into a review. The other reason is that I wish an article like this existed when I was trying to get into jazz. An article that gives fans of the harder side of rock music a guide for getting into jazz without the snobbery of some of the more traditionally-minded jazz media – hopefully. This also means that the artists I will be discussing in this first chapter will be electric jazz musicians, with the focus on the jazz-rock and fusion scene of the late sixties and early seventies.

The reason why I think this scene will be of particular interest to fans of rock music trying to get into jazz is simply because it was the first time rock music and jazz came together. Also, I tend to prefer the textures of electronic keyboards to the sound of an acoustic piano, at least until smooth synthesizer sounds sanded the edges off the more rock-inclined jazz artists around the early eighties. So while this guide will not help you get acquainted with the discographies of old jazz heroes like John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie or Duke Ellington, I thought another huge name in jazz would be the ideal place to start.

Miles Davis’ Electric Period

Miles Davis is the perfect artist to start with, because – spoiler alert – most of the other bands and artists covered in this article relate to him in one way or another. In a way, this should not be too surprising, as the trumpeter and band leader was at the center of almost every major development the genre went through during his lifetime. His 1959 release ‘Kind of Blue’ is widely considered to be the greatest jazz album of all time. And while I personally don’t even think it is the greatest record of the era when he was still playing purely acoustic music, it does say something about the influence Davis had on other jazz musicians, as well as his immense popularity.

During the late sixties, Davis was introduced to rock and funk by his then-wife Betty. Sly and the Family Stone, James Brown and Jimi Hendrix were particularly influential and he tried incorporating rock elements into his music. The first careful steps towards a more electric interpretation of jazz were taken on his 1968 releases ‘Miles in the Sky’ and ‘Filles de Kilimanjaro’. But the following year’s brooding masterpiece ‘In a Silent Way’ is seen as a turning point in both Davis’ career and the history of jazz. All keyboards on the album are electric and John McLaughlin’s electric guitar is featured prominently on the album.

Stylistically, ‘In a Silent Way’ feels relatively traditional, but many jazz critics felt like Davis was selling out to the rock audience. Ever the stubborn guy, Davis dove head-first into electric music for his next recording session, which resulted in the abstract, psychedelic bestseller ‘Bitches Brew’. While ‘Bitches Brew’ is the first Miles Davis album with very pronounced rock elements, it isn’t the best record to get familiar with his work. The long songs have very little in the way of traditional structure and recognizable melodies. And while it is a rewarding listen once it sinks in, it might take a while before it will get there.

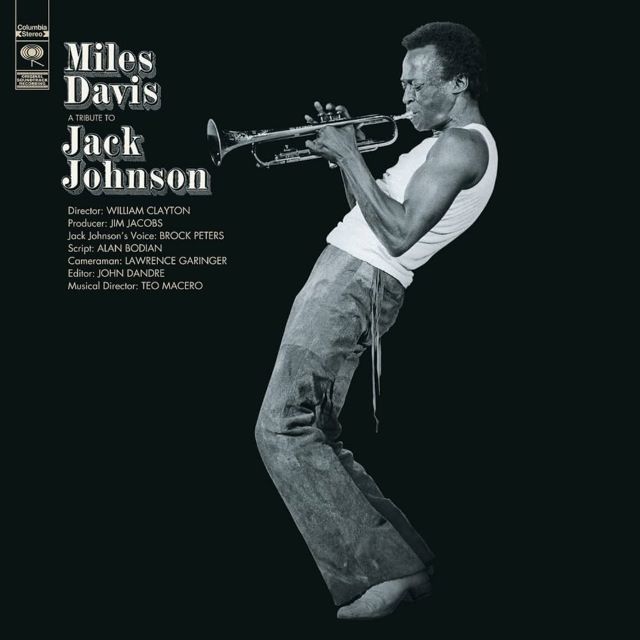

Easier to digest and in my opinion Davis’ best studio recording is ‘A Tribute to Jack Johnson’ (1971). This soundtrack for a documentary about the titular boxing legend feels closer to a true fusion of jazz and rock. McLaughlin is playing riffs rather than textures, while bassist Michael Henderson and drummer extraordinaire Billy Cobham lay down a really solid rhythmic foundation. Both pieces on the album are over 25 minutes long and full of lengthy improvisations, but have a decidedly rock ‘n’ roll feel that truly benefits the music.

Miles Moves from Rock to Funk

Throughout the rest of the early seventies, Davis’ fascination for funk and African rhythms increased, resulting in an album quite likely even more controversial than ‘Bitches Brew’ in 1972’s ‘On the Corner’. There are probably no albums in my collection with fewer melodies. And yet, the complete devotion to rhythms makes the album sound unlike anything released before or since. It’s not exactly funk, but it’s gritty, it’s greasy and it certainly sounds less intellectual than anything Davis had done up until that point. Once again, not an easy album to get into, but worth it if you get a kick out of cool rhythms.

During these years, Davis’ performances were frequently made into live albums. Whether or not those are worth having depends on your personal opinion of whatever Davis was doing at the time. But for what it’s worth, ‘Agharta’ is one of my favorite Miles Davis releases. The band Davis was working with at the time was incredible, with guitarists Reggie Lucas and Pete Cosey doing a lot of the heavy lifting. Cosey is one of the unsung guitar heroes of the era, basically taking Hendrix’ innovations to the extreme. And while the long tracks on ‘Agharta’ and its counterpart ‘Pangaea’ are as abstract and full of improvisation as most of Davis’ other seventies work, they also feel somewhat more structured and have a truly unique atmosphere.

Shortly after the performances on ‘Agharta’ and ‘Pangaea’, Davis retired from music and basically became a recluse for multiple years. He did briefly make his way back to the spotlight in the eighties, again following a different musical path inspired by funk and early hiphop. Occasionally interesting, but the rock influences would not return.

Herbie Hancock and The Headhunters

Herbie Hancock has a somewhat odd relationship with electric jazz. After being introduced to the electric keyboard during his time playing with Miles Davis – reluctantly, by his own admission – he spent a while creating music that was even more abstract and spacey during what came to be known as his Mwandishi period. This period lasted three albums and was named after the first from 1971 – as well as the Swahili word for composer. While the music on ‘Mwandishi’, ‘Crossings’ (1972) and ‘Sextant’ (1973) was more composed than anything on ‘Bitches Brew’, in the sense that it has more recognizable parts, the overall sound is even less accessible, resulting in disappointing sales and what seems like a premature end of the style.

This is made all the more apparent by 1973 classic ‘Head Hunters’, which sees Hancock and his band – including the fantastic bassist Paul Jackson – incorporate funk elements into their sound. Hancock was so inspired by Sly and the Family Stone that he even named one of the tracks on the album ‘Sly’. It barely sounds like them or any funk that was around at the time, but it’s definitely more funk or even proto-hiphop than most other jazz music flirting with funk at the time. Next year’s ‘Thrust’ successfully expanded upon the formula set on ‘Head Hunters’ by adding a more pronounced melodic layer, which is part of why I prefer it to ‘Head Hunters’.

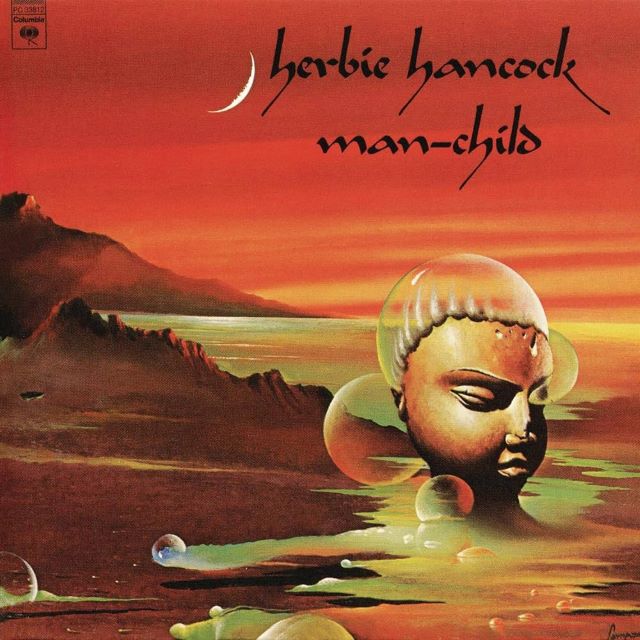

‘Man-Child’ (1975) saw Hancock do what he should have done from the moment he went electric: he added guitars to the mix. And not just any guitars. Motown veteran Wah Wah Watson, later Funkadelic contributor DeWayne ‘Blackbyrd’ McKnight and David T. Walker, who worked with the likes of Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, all recorded guitar parts for the deliciously funky ‘Man-Child’, which is easily one of my favorite jazz-related albums of all time.

Unfortunately, ‘Man-Child’ proved to be the peak for Hancock’s fusion period, as 1977’s ‘Secrets’ is a significant step down and he would increasingly experiment with electronics in the following years. Still, Hancock’s early seventies albums, as well as the albums his backing band The Headhunters recorded without him, are worth hearing for rock and funk fans getting into jazz.

Return to Forever

Return to Forever is my favorite jazz-ish band and likely the one closest to traditional rock music in terms of composition and line-up. They did have a bit of an odd history, however. The band started as a vehicle for Chick Corea, who worked with Miles Davis throughout the late sixties and early seventies. In fact, ‘Return to Forever’ was originally the name of Corea’s 1972 album, which along with its follow-up ‘Light As A Feather’ is rooted in latin and Afro-Caribbean music rather than rock. If you want to know whether a Return to Forever album is worth checking out, the simple answer is: it is if Lenny White plays on it.

White is one of my favorite jazz drummers because he truly understands rock grooves. He hits harder than the average jazz-rock or fusion drummer, but he understands the nuance of the jazz idiom as well. His debut with the band was the 1973 release ‘Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy’, which immediately shows why Return to Forever has more crossover appeal than Miles Davis had. While there is still plenty of room for lengthy improvisations, there are actual riffs and rhythms on the album, structured in a way comparable to what a relatively adventurous seventies rock band would do. There are more melodies and the album has a sense of memorability that truly makes it stand out among its peers.

The classic line-up of Return To Forever was formed when Bill Connors left the band and a young guitar prodigy by the name of Al Di Meola joined the band. While Connors was great at translating jazz to a rock idiom, Di Meola’s dexterity and actual background in rock and classical guitar makes him sound like a precursor to heavy metal lead guitar at times, even more so on his first couple of solo albums. In Return to Forever, his interactions with Corea and especially bass virtuoso Stanley Clarke turn ‘Where Have I Known You Before’ (1974) and ‘No Mystery’ (1975) into hard-driving, yet sophisticated musical cocktails rarely heard before or since.

‘Romantic Warrior’ (1976) is considered to be a classic of both fusion and progressive rock and while I think its predecessors had better highlights, it can be considered a peak in both composition and musicianship for anyone involved. Corea felt this particular instalment of Return to Forever had run its course and decided to carry on without the rock muscle of White and Di Meola. The reunion live releases ‘Returns’ (2009, with Di Meola) and ‘The Mothership Returns’ (2012, with Frank Gambale on guitar and Jean-Luc Ponty on violin) are powerful reminders of how well this group of musicians worked together.

Mahavishnu Orchestra

One cannot talk about fusion without mentioning John McLaughlin. The British-born guitarist was already immortalized as a pivotal figure in electric jazz through his work with Miles Davis and longtime Davis drummer Tony Williams before starting his own band. But it was Mahavishnu Orchestra that truly cemented his reputation, as well as the value of the electric guitar in jazz music. The first Mahavishnu Orchestra line-up in particular is responsible for some of the strongest fusion ever released. Where Return to Forever generally sounds riffy and down to earth, Mahavishnu Orchestra has a rather unique ethereal vibe.

‘The Inner Mounting Flame’ (1971) and ‘Birds of Fire’ (1973) are classic fusion albums on which the melodies of McLaughlin and the electric violin of Jerry Goodman create a fairly unique sonic pallette with a somewhat psychedelic character. Shortly after ‘Birds Of Fire’, the original line-up of Mahavishnu Orchestra fell apart and the band slowly morphed into a solo venture for McLaughlin. Good, but not as magical as the first two albums. However, in 1999, ‘The Lost Trident Sessions’ was released. It was recorded in 1973 and featured the original line-up. McLaughlin plays uncharacteristically straightforward riffs on that album at times and as such, it is recommended to rock fans trying to get into more jazzy territory.

All members of the original Mahavishnu Orchestra line-up had success away from the band. Most famously, keyboard player Jan Hammer wrote and performed music for ‘Miami Vice’. McLauglin continues to create interesting music to this day, even appearing on one of my favorite albums of all time: the all-acoustic ‘Friday Night In San Francisco’, recorded with Al Di Meola and flamenco legend Paco de Lucía. But the best Mahavishnu-related solo album is drummer Billy Cobham’s debut ‘Spectrum’. The album features all the muscle of rock music and all the unpredictability of jazz, as well as spectacular guitar work by Tommy Bolin. Cobham’s more funky work of the later seventies is also worth exploring.

Magma

Sure, calling Magma jazz is stretching it a bit, but that’s exactly what makes them such a great gateway band. Depending on who you ask, Magma will be labelled as either progressive rock, jazz-rock or zeuhl, the latter being the genre description first coined specifically for Magma’s unusual mix of influences. Their first two albums are reasonably traditional jazz-rock, albeit with fairly unconventional vocals in a partially improvised constructed language. It wasn’t until the lead-up to their third album ‘Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh’ (1973) that drummer and main composer Christian Vander truly found Magma’s completely bonkers sound. A sound that may require some time and might not ever make sense.

The foundation on ‘Mëkanïk Dëstruktïẁ Kömmandöh’, ‘Ẁürdah Ïtah’ (1974) and ‘Köhntarkösz’ (1974) consists of Vander’s thunderous, at times almost militaristic rhythms and Jannick Top’s massive distorted bass sound. Due to the revolving cast of musicians, the exact instruments on top of that foundation differ from release to release. But there is always room for idiosynchratic choral vocals that occupy a space somewhere between haunting gospel and contemporary classical music. Most of them sung in the constructed language Kobaïan, which makes them sound like additional melodic instruments rather than traditional singing. Often, though not always, the singers and band – including Vander’s drums – play in some kind of hypnotic unison.

For the longest time, ‘Üdü Ẁüdü’ (1976) was the only Magma album I owned. Closing track ‘De Futura’ is a masterpiece and the album as a whole feels a bit more accessible. ‘Attahk’ (1978) overall feels like a more traditional fusion record, with its looser rhythms and its clear influences from African-American music. Vander laid Magma to rest in the mid-eighties, but rebooted the band about a decade later. Since then, Magma frequently released new material ranging from good to excellent, often using reworked versions of compositions that were performed, but never recorded in the seventies. Especially the live and studio releases with guitarist James Mac Gaw – who sadly died last year – and bassist Philippe Bussonnet are very much worth hearing.

Stay tuned for the second chapter, which will feature some more contemporary jazz artists that a rock audience might enjoy.

Leave a comment